The morning air was crisp and expectant as I put my bag and hiking shoes into the car. Fort Portal, with its misty hills and tea plantations, was slowly waking up around me. My destination: Semuliki National Park, a hidden gem nestled against the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo in Uganda’s western region.

The journey from Fort Portal to Bundibugyo district winds through the Rwenzori foothills, a route that defies ordinary description. As we climbed higher, the landscape transformed dramatically—verdant slopes giving way to massive stone formations that seemed to stand guard over the valleys below. These natural sentinels, weathered by centuries of rain and sun, appeared to welcome travelers into a realm where Uganda’s wilderness meets Congo’s untamed territory.

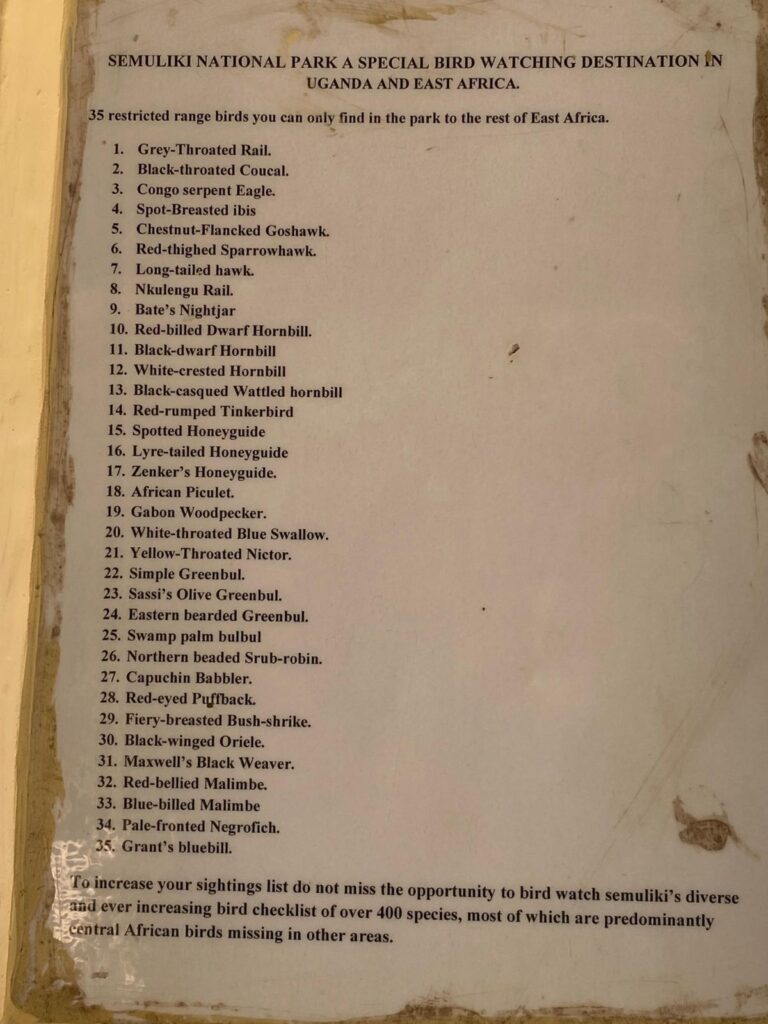

After one hour and 20 minutes of hairpin turns and breathtaking vistas, the entrance to Semuliki National Park appeared—a modest gateway to one of East Africa’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Here, the transition between the great Central African rainforest and the East African savanna creates a unique ecological melting pot.

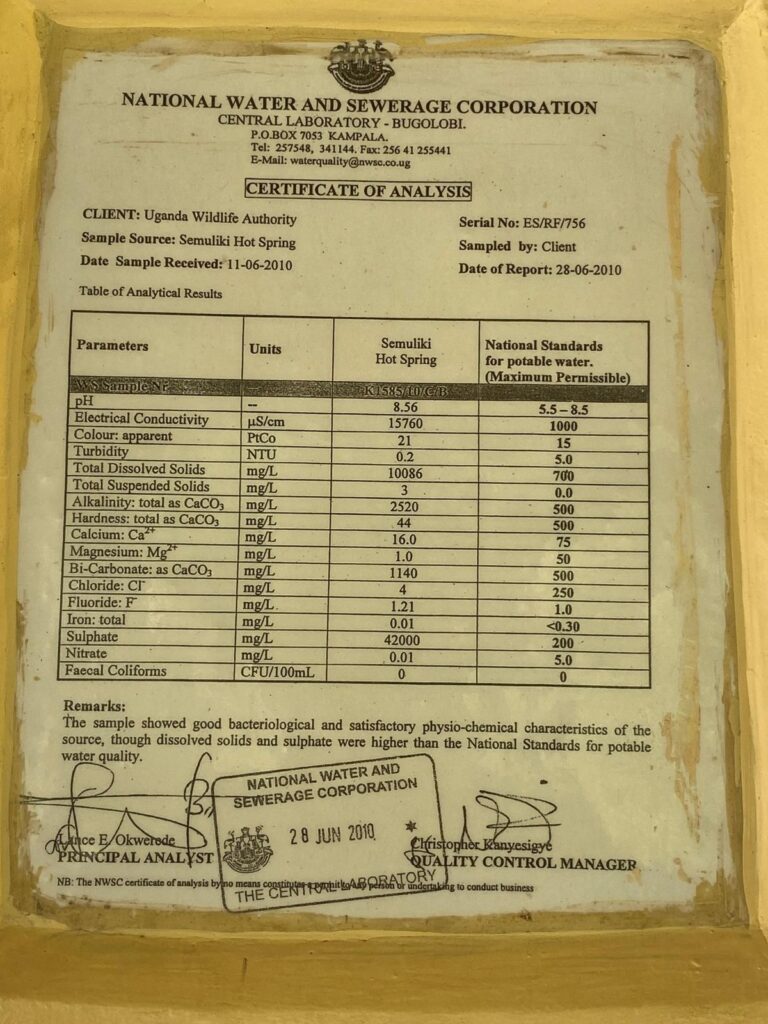

This park is home to the Male and Female Sempaya hot springs, which are found nowhere else in Uganda,” explained my guide, James Akankwasa, as we paid our park entrance fees. His eyes sparkled with the pride of someone who has dedicated his life to preserving this natural wonder. “What you’re about to see are the first hot springs”.

Our first destination within the park was the famed Sempaya hot springs. The trail leading to these geological marvels cut through dense forest, where shafts of sunlight penetrated the canopy to create dappled patterns on the forest floor. The humid air carried a cocktail of scents—decomposing vegetation, mineral-rich soil, and an increasingly prominent note of sulfur.

“The springs are divided into ‘male’ and ‘female’ sections,” Akankwasa explained as we walked. “Local communities have revered these waters for generations. They’re not just natural phenomena but sacred sites.”

The female spring, known locally as “Nyasimbi,” came into view first—a bubbling pool approximately twelve meters wide surrounded by a cloud of steam that danced in the morning light.

The water boiled ferociously, occasionally shooting jets several feet into the air. The surrounding vegetation had adapted to this harsh environment, creating a stark contrast between the scalding spring and the lush rainforest.

“You can boil eggs here,” he demonstrated, carefully lowering a crate containing eggs into the less turbulent edges of the spring. Within minutes, they were perfectly cooked—a surreal cooking demonstration in the heart of the wilderness.

After seeing the female springs, we had a short walk along a wooden boardwalk that crossed a swampy area teeming with life to the Male springs called Biteete. Unlike its female counterpart, the Biteete surrounding area was painted with mineral deposits in striking hues of orange, yellow, and white.

As we observe these natural wonders, Akankwasa shared the local legend behind their naming—a tale of star-crossed lovers whose forbidden romance led to their transformation into these eternal springs.

According to tradition, Biteete and Nyansimbi were lovers from different clans whose families forbade their union. When they attempted to elope, ancestral spirits transformed them into the hot springs, forever separated yet eternally connected through the underground thermal channels.

“Some local elders claim that on particularly quiet nights, you can hear them calling to each other,” he revealed in a hushed tone that made the hairs on my arms stand up despite the tropical heat.

Being near the DRC border gave the entire experience an edge of the exotic. Standing at certain viewpoints, I could see the natural boundary where Uganda meets Congo—not a fence or wall, but a subtle shift in the landscape that has witnessed centuries of cultural exchange and migration.

“Many of the local communities have relatives on both sides of the border,” Akankwasa mentioned as we paused for lunch at a scenic overlook. “The colonial boundaries meant little to people who have moved through these forests for thousands of years.”

The day concluded with a sunset viewing from an elevated platform overlooking the Semliki River, which forms part of the border with the DRC.

Semuliki National Park may not claim the fame of its cousins like Queen Elizabeth or Murchison Falls, but therein lies its magic.